When he turned 80, at the beginning of March last year, Günther Bosch’s name appeared again in the German sports newspapers. He hasn’t been forgotten: Günther Bosch, the coach who helped the teenager Boris Becker win Wimbledon twice; Günther Bosch, one of the most important people in German tennis, which is still waiting for the next Graf and Becker; Günther Bosch, the tennis commentator and expert that German journalists regularly call. But as much as Bosch is known and revered in his country of adoption, he is virtually unknown in his native Romania. Very little has been written about him, his achievements and his „legacy” – a theme he is more and more concerned with these days: can he leave something for Romanian tennis as well?

*

The Rot-Weiß Tennis Club in Berlin, the last place where Günther Bosch coached, is very special for tennis culture in Germany. Built a few years before the 20th century, Rot-Weiß (Red – White) is still somewhere between the romantic tennis era and the present. An entire sports venue – 16 courts plus the 7,000-seat Steffi Graf Stadion – is hidden on the edge of the Grunewald district to the west of Berlin, a neighborhood of large mansions built in the neoromantic style, complementing the surrounding nature. And if there were no modern cars gliding by, you might think you went back in time, between the two World Wars.

Günther Bosch was born two years before the Second World War in Braşov, Romania. That town has as much in common with today’s Brașov as tennis back then had in common with the tennis played now. And if his hometown has moved from industry to tourism, putting on a more bohemian mask, his favorite sport went in the opposite direction. To follow Bosch’s path in tennis means to follow the changes that this sport has grumblingly accepted in the last 60-65 years. It is a useful exercise for anyone who wants to sneak a peek into the future of the game, because you cannot know where you are headed unless you know where you started. It’s about trajectory, just like in tennis: once the possible trajectory of the ball is understood, its final destination no longer surprises you. And yet. No one could anticipate Bosch’s tennis destination.

*

A student at the German School, the young Bosch first stepped on a court to gather tennis balls for wealthy people of Brașov. It a was a way to make some money for sports shoes, a very important goal for any active kid. And all the kids were active then. „People in Brașov used ski, skate and play hockey in winter, and play a ball sport during summer,” says Bosch. His father, a pretty good gymnast who was part of the well-known Bosch family (the company with the same name was founded in Stuttgart in 1886), was invited by the owner Robert Bosch to a sort of competition – everyone played the sport they knew. Gunther practiced different sports until he was 15, when he had to choose between tennis and basketball. He chose tennis.

He was denied enrollment in high school because his father was not ”working class” enough (he was the head of a food warehouse near the Bartolomeu railway station). Fortunately, the warehouse had some tennis courts where the young Bosch was the ball boy. When the courts were free, he played with the other ball boys. „I had some talent. I remember one morning, a bank director living in one of the villas nearby called me and threw me a wooden racquet over the fence. It was in bad shape and I had to tie it with wire, but even so, it was extraordinary. ”

Soon he started playing for the Red Flag Sports Club, which belonged to the factory with the same name. There he met Ion Tiriac. He saw him playing table tennis, but he already knew him, because they lived on the same street. „I thought: since he is good at table tennis, he can’t miss the ball with the big racquet.” From there on, their paths went in the same direction.

*

„My first trip abroad was to the French Open, in 1958. De Gaulle had come to power, there were riots on the streets and we were not allowed to leave the hotel.” But it was their first trip abroad, they were young and stayed right next to the Arc de Triomphe. How could they stay inside? Especially since there were so few chances to play big tournaments. At home, eight players played each other, three out of five set matches – and the first two or three were sent to the French Open – so by the time they got to Paris they were dead tired. The system in the pre-Open era worked on recommendations. „If you were a Davis Cup player and if you had some important victories in your resume, then you could take part in tournaments abroad. Of course, if you wanted to go to Western Europe once, you had to play in Moscow, Sofia and Warsaw, too. But we enjoyed it, we were happy to go anywhere, because very few people traveled back then. „We were always escorted by the ”man of the system” (somebody who worked for the secret police), but we had bigger problems than that. „Before we left, all the higher-ups in the Federation told us what to bring them: nylon stockings for the wife, clothes, cigarettes and so on.” They had to live on a two-dollar allowance per day, so they packed two tennis kits, and then filled the rest of the suitcases with canned food, so they will not have to spend the money in restaurants. „Back home, no one cared if we lost (and we lost early on). They were pleased that they received their gifts … They couldn’t wait for us to lose!”, he laughs.

But life was beautiful. He was traveling more and more, he met new people, places and customs. „Once I played in Athens, where the matches started at 10 p.m. and lasted until morning. It was something special. I played at two or three at night, and the stands were so full. We were wondering how those people would get up for work the next day. ”

/>

/>Thanks to excellent footwork, Günther Bosch reached all the balls and he liked to hit them flat and hard. Tiriac, on the other hand, played „moonballs” or ”junkball tennis” – as they say. „He hit the ball back until the opponent missed,” says Bosch. „I remember the first time he beat me in Cluj, at the national championships. I had beaten him in practice just a few days before, easily! And in the tournament he hit the ball higher and higher until I missed. That defeat was very hard to swallow… Anyway, Tiriac was the type of man who caught on very quickly…”

And he had plenty of opportunities and people to learn from: while tennis today is by definition an individual sport, their tennis was a team sport. They represented the club in the team division, a very important, prestigious competition.. „The Red Flag factory hired me to work only four hours, the other four hours I had to train. My job was to check ball bearings. I also helped Tiriac to get a job, but in another department. He stood on a heap of balls coming out of the heat treatment, after they cooled a little, and he counted them: 5, 10, 15. It was hard but he bought a tennis racquet with his first paycheck. It was a special thing for those times, „says Bosch, while he pulls out a picture of Tiriac on a motorcycle: „I went with him on his motorcycle to a tournament in Sibiu. Dear God, he was driving so fast! But brave as he was on a motorcycle, he was scared shitless of going to the doctor, for example.”

Bosch talks a lot about Tiriac. He describes him as an old friend and tells you a lot of stories about their common passion, tennis. Once, Bosch had surgery on his foot (the soles of tennis shoes was so thin that after playing two or three times the players had blisters and tears). Tiriac carried him on his back when he was discharged from the hospital, for three bus stops, the last one uphill.

”So you were good friends?

”No, we weren’t. Tiriac never called me ‘Günther’. He called me ‘Bosch’, but most of the time he called me ‘Saxon’. And later he called me ‘traitor’. That was Tiriac…”

*

Günther Bosch was not the best Romanian tennis player. Between Gheorghe (Gogu) Viziru, who was still playing, and the up-and-coming Ilie Năstase and Ion Ţiriac, the competition he faced was tough. But he managed to come in the third place in the Davis Cup team and achieve his greatest goal: to win the Romanian International Championships. „This was the most important tournament for us.” He did it after he beat Tiriac in the semifinals and Gogu Viziru in the final. „It was a really big surprise,” says Bosch, „because people believed Viziru was unbeatable then.”

He does not remember exactly how long he continued to play tennis after this success. Not long. Instead, he signed up for coaching classes. The topic for his diploma exam was the psychology of the tennis game. „I did a psychological analysis of the serve: mentally, how should a player prepare for the serve? What must go through his head to make his serve a major weapon? It was a great thesis.” It was translated into German and Czech, and Bosch was invited to present it at several seminars in Moscow, Budapest and other countries. „Everyone was surprised because there were descriptions of the serve from a technical or tactical point of view, but not from a psychological point of view.”

He was interested in this topic because his serve was his his weakest shot. It was too late for Bosch the player to take advantage of the new knowledge, but Bosch the coach was going to profit from it.

*

After graduating from the coaching school, Bosch was quickly appointed as a state coach (federal, as it is called today). „But my name was Günther Bosch, and Ceausescu was bothered by this. I was not allowed to sit on the bench during the Davis Cup ties and they kept telling me: ‘if you want this, you have to change your name to Boşescu.’ ” I did not accept. The Federation named Marin Viziru, Gogu’s twin brother, for the Davis Cup, and Bosch began to think seriously about leaving the country. An opportunity presented itself very soon, when the Federation challenged him to win the position of coach for the Galea Cup, one of the most popular junior competitions of the time. „The Federation told us that the coach who managed to find four juniors good enough to represent Romania at the Galea Cup will accompany the team abroad.” Bosch took his boys from the Red Flag, found someone else from Constanța and took them all to Tennis Club Bucharest. „They were so good that the Federation had no choice but to allow us to represent Romania at the Galea Cup.”

In 1974, the competition was played in Saarbrücken, Germany, and Bosch – who could easily prove his German origins – remained there. „In Romania, besides my wife, nobody knew, not even my parents or my in-laws, no one. The boys played well but did not win. And when I took them back to Frankfurt, I gave them all the receipts and told them I was going to stay in Germany to play some senior tournaments. Perhaps some of them suspected something … ”

Bosch, who had played in Germany several times, was already known in the country that continued its economic development started after the end of World War II. So his timing could not have been better. „When they heard I was in Germany, the president of the German Tennis Federation called me immediately and asked me to come to Hanover (their headquarters). They needed a federal coach from the beginners to the juniors, and I could train the seniors team in Hannover, too. This was an excellent job, I could not believe it.” But if Bosch’s coaching problems were solved now, his family problems were just beginning.

*

Immediately after leaving Romania Bosch was sentenced, in absentia, to seven years in prison. He says his family suffered enormously. „My wife participated in the trial, she had to listen to what they were saying about me. Every week she was called to the Securitate headquarters (the Romanian secret police) and was pressed to say if she had known I was going to defect. If she had admitted to that, she would have gone to prison right away.” Their apartment was confiscated and both his wife and daughter had to start from scratch without him. Instead they had a stranger in front of the house who followed them around. For three years they were separated and Bosch did everything in his power to bring them to Germany. „I wrote letters to all ministers in Germany, and the only one who answered was (Helmuth) Kohl, who was not yet Chancellor. He told me he would first visit (Iosip) Tito in Yugoslavia, and after that he was going to Bucharest and would try to present my case to Ceausescu.”

When he wrote again, Kohl said that Bosch’s family would be in Germany in two weeks. Bosch called his wife, as he did every Sunday, knowing full well that all the conversations were recorded. They could not believe it: she had been summoned to interrogation just one day before and was told to ask for a divorce, otherwise she would bear the consequences. Instead, she and their daughter suddenly received the paperwork for traveling. Kohl had succeeded. „My wife asked me what to bring. I said, ‘Do not bring anything! I have been working 12 hours a day and you can buy whatever you want. Indeed, in a few days I went to Frankfurt and picked them up from the airport. They soon received German passports.”

*

The first years of coaching in Hanover, when he was still alone in Germany, meant a lot of work. First of all, he had to quickly shake off his Romanian coaching habits and learn how to work with German players. It was not easy. „In Romania I pushed my players very, very hard. I did not have a racquet in my hand, but a stick. If they did not get the footwork right, if they did not move properly on the baseline, I would hit them with the stick. That was the style in Romania. Being a coach meant being a kind of dictator.” In Germany, he had to learn the democratic style and turn from a dictator into a mediator. Instead of bossing the players around, he had to convince them with arguments, explain and answer their questions.

He did not train at -25 degrees, as he did in the Romanian mountains; he did not punish his players with herculean tasks, he did not ask them to climb ten times in a row to the top of snow-covered fir trees just because one of them broke curfew. But he continued to remain a strict coach, he worked with the players on Christmas, he applied some of the old training methods and added all the advantages of Germany’s prosperity and openness: equipment, technology, access to information.

In the late 1970s, the main federal coach was Richard Schönborn, who had also defected, but from Czechoslovakia. He worked for more than 25 years in the Deutscher Tennis Bund (DTB) and he published many tennis books. Schönborn was an outstanding theorist, but he did not care much for practice. That was Bosch’s job. And after one of the winter camps where the German team prepared for the King’s Cup (launched by King Gustav V of Sweden in the 1930s and cancelled in 1985, a sort of indoor Davis Cup) the players rebelled. „They said, Bosch works with us, runs with us, and Schönborn comes back from the holiday and wants to take over. We no longer accept him as our coach. ” And as the players had a say, DTB made the switch: Bosch accompanied the team to Essen for the King’s Cup, and Schönborn went to coach the juniors in Hanover.

From then on, Bosch’s career took flight. At a time when France played with Yannick Noah and Henri Leconte, Sweden had Joakim Nyström and Stefan Edberg, and Britain and the other countries participated with their best players, Bosch led his team to two King’s Cups (Germany has won a total of four trophies). „I remember that in one of the finals we defeated the Czechs, who had (Ivan) Lendl, the world’s number one,” says Bosch. His results in King’s Cup recommended him for the position of Davis Cup coach. For a guy who had not been accepted on the Romanian Davis Cup team, he was doing very well.

In 1982, after five years of successfully coaching the German Davis Cup team, Bosch was replaced. It was Schönborn’s turn to take over the men’s team, and Bosch was to work with the Fed Cup female team. „At the time we had three female German players in the top 10 and one of them had won the Masters tournament in New York. But I said, „I don’t need to torment women with my style.” I wanted to stay with the men’s team, but they did not accept. ”

Many people urged him to use his prestige to start a private tennis school. „I thought: back in Bucharest, when they kicked me out of state coaching, what did I do? I took four juniors and worked with them until some of them broke through. Let me do the same thing in Germany. And I was lucky that the Federation accepted my proposal. ” It was an inspired move. All tournament expenses, including those in America and Australia, were to be paid for by DTB, the whole training system was well established, so Bosch chose four young players. Among them, a certain Boris Becker.

*

He had first noticed him in 1976. The federal coaches had to conduct a trial each fall for the kids who wanted to be accepted into the Federation training camp. At one of these trials in southern Germany, he saw and selected Becker for the first time.

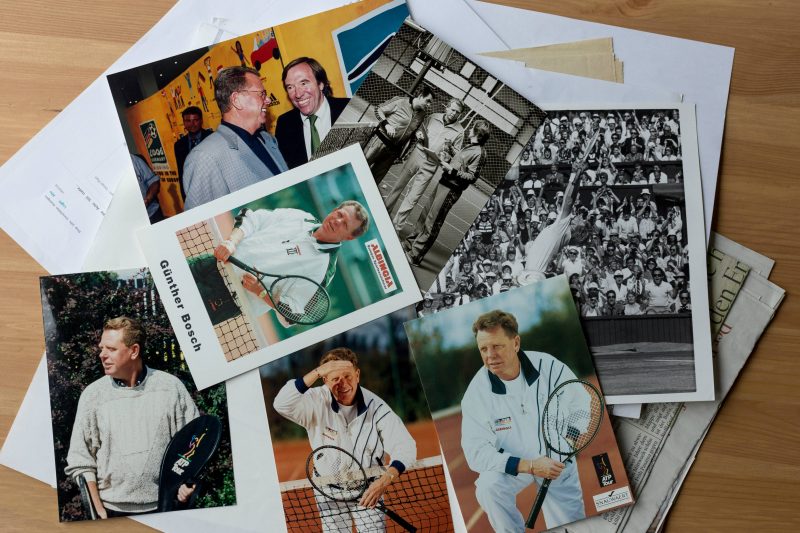

Boris Becker started to play tennis at the Baden Tennis Center in Leimen, a suburb of Heidelberg (Baden-Württemberg). Everyone knows he trained there with Boris Breskvar, one of West Germany’s most renowned coaches, but Becker’s discovery is very controversial. Bosch has a newspaper cut-off from October 7, 1976: a picture of him together with Schönborn, Breskvar, other coaches and a few children, almost all blonde, almost all skinny. Among them, Boris Becker (nine) and Steffi Graf (eight).

„I chose Becker,” says Bosch, „but the head coach said he was not ready for the national team and he should keep training within the local federation.” At the following meeting, attended by all 13 federations of the German Länder, Bosch stood up and once again proposed Becker. „But what are your arguments?” he was asked, because in the data sheet he had written that Boris was too fat and barely moved. „Indeed, those kids who tried for the team came prepared. They did 50 squats and push-ups, Becker could only manage 30; he was among the last in the 30-meter sprint. So he was not physically fit. But I thought he had a tremendous discipline in hitting the ball; he had a special look, a special anticipation. When the ball was in play, bombs could fall around us, he did not care; he was focused on the ball and the movement needed to send the ball where he wanted. He had special psychological qualities; he may not have known how to run, but he knew when the opponent was about to hit a short ball and left early, so he got to all of them.” They accepted him.

Boris, the kid they laughed at when he was struggling to get to a ball and threw tantrums, had entered the accelerating environment of the German Federation. „But I was with the Davis Cup team too, I was not involved with Becker too much. He came to practice with his mother, and I saw him. You felt pity when the others laughed at him, but he took his revenge when they were playing soccer or hockey: he would break them all, he was a beast on the court. ”

It was not until 1982, when Bosch completed that group of four young men by selecting Boris, that the two began to work seriously. And even then he did not receive special treatment because Bosch treated his entire group the same way. „This four-player group thing, I’ve got this idea from an Australian coach that is said to have been the best of all time: Harry Hopman.” Bosch thought that if one of the four will break through, then he will continue only with him. And he saw in Becker qualities that others did not have. „To become a great player you have to play differently, it’s true to this day. Now, except for Federer, everyone plays the same. Without special ideas, they stand on the baseline and hit the ball over the net until the opponent misses. It was the same then. Everybody said Borg was great, so I wanted to see how he plays. I was standing by the court, watching him: 15 minutes, 30 minutes, it was the same thing! Sure, you have to respect it, because results matter. ” But to have results against players like Borg, Bosch knew Becker had to do something different. And he focused primarily on the serve. „I returned to my diploma paper, looking for the best service motion for him. I do not know if you remember but Becker was landing with his right foot in front of his left, something I got from Hopman, who had taught it, among other players, to (John) Newcombe. I had been looking for a service motion that suited Boris, and this extra step allowed him to get to the net faster. ”

*

While Becker was still a work in progress, Tiriac was traveling with Guillermo Vilas, who was very successful under his guide. Vilas ranked in the top 10 between 1974 and 1982, with a career high at number 2, and won four Grand Slam tournaments over the same period. „Tiriac and I met and talked on the tour, and he told me: “Saxon, you’re a coach in the country with the greatest financial resources, with an extraordinary industry, it’s impossible not to find a promising German junior.” Tiriac wanted to expand into Germany, because they had the strongest sponsors. But for that he needed a great player,” says Bosch. He showed Becker to him in Monte Carlo, where the junior tournament was played at the same time as the seniors.

Boris, who was playing a close match against another Bosch player, lunged to every ball, to the left, to the right, and looked more like a football goalkeeper than a tennis player. „He was covered in clay, he had that hair, he looked like a mess! And Tiriac, after looking at him, told me ‘this is a farmer, what do you want to do with him in tennis? He can be a mayor in his village, not a tennis player. ”

But Tiriac changed his mind a few days later when the same Boris Becker, playing impressively, won the final. „He told me I may be right about Becker, and he asked me to contact Boris’ parents.” That was not a simple matter, since Becker was already courted by agencies such as IMG (and its influential founder, Marc McCormack), but Bosch put in a good word for Tiriac. He told them that unlike the agencies that have hundreds of players, Tiriac – who only travels with Vilas – could focus only on him. Boris would not risk becoming one among many. „But when they saw Tiriac for the first time, they told me he looked like a carpet salesman. I told them he had a great tennis soul, that he had a lot of tennis courts, a big fortune, tennis clubs in Wiesbaden, Zurich, New York. Soon, they were convinced. ”

Boris lunged to every ball, to the left, to the right, and looked more like a football goalkeeper than a tennis player. „He was covered in clay, he had that hair, he looked like a mess! And Tiriac, after looking at him, told me ‘this is a farmer, what do you want to do with him in tennis? He can be a mayor in his village, not a tennis player.”

The next stop was the German Federation, which had financed Becker’s group of four. When they announced that Boris was withdrawing and Bosch resigned as a federal coach, the sports director replied that this was not possible, that they had invested a lot of money in Becker. „But how much did he cost you, how much do you want?” Tiriac asked. When the director of the DTB responded, hesitantly, that it was somewhere around 25,000 marks per year, Tiriac suddenly pulled out his checkbook. „The guy got scared, you can imagine (laughs). He said, „I’m not allowed to receive a check, that is not legal in Germany.” Bosch was surprised by Tiriac’s gesture, but the Federation had no choice but to accept the separation from Becker, on the condition that Boris play a Davis Cup match without pay.

„Besides, I had another problem: I had a very profitable contract with the Federation. I will not mention the amount, but what Tiriac offered me at first was a quarter of what I was getting from them. Everyone told me that I was crazy: ‘How can you leave the Federation when you have a lifelong contract? You will go away and only work with this crazy man?’ – that is, with Becker. ” Bosch knows it would be easy now to say that he always knew Boris would win Wimbledon, but the truth was that neither he nor Tiriac could be sure Becker would become a great player. They just knew he had something special. Bosch remembers a doubles final that Becker played in London when he was still a junior. „He played with (Emilio) Sánchez against Lendl and (Andres) Gomez. I think they were number one and number five in the world. Any junior would have been afraid, he would not have been able to hit a single ball. Boris played an incredible match and the public went crazy. But he did not care about the public, or Lendl, for that matter. He only cared about the ball coming his way and how to hit a winner off it. It was fantastic! On such clues did Bosch base his decision to work with Becker, but those around him only saw it for what it was: a very risky move.

Becker, Bosch and Tiriac signed a partnership agreement in 1984 at Roland Garros, but the first steps were not easy. Bosch barely received a quarter of the money he had received from the German Federation, and Becker’s performance was very up and down. „In Johannesburg, he did not want to wear a cap. Obviously, he got heat stroke and had to withdraw. So we made that trip to lose in qualifications. ”

But they went to Australia, where at that time the tournament was played on grass. And grass was a perfect fit for Boris. „Indeed, he gets to the quarterfinals after beating (Guy) Forget, and Tiriac says “This I can sell: such a young junior makes the quarterfinals in the mens’ tournament.” He got deals with Rot-Weiß Berlin, Adidas, Elesse, and those could pay for everything. I was going to get my money, too, and of course I had a percentage of the prize money and the contracts. ” Again, things were looking good for Günther Bosch. And they were going to get better.

You cannot talk to Bosch without touching on Becker’s success at Wimbledon. But in his first appearance on the main draw in 1984, the kid, who was not yet 17 years old and had come through qualifying, had to withdraw in the first round against Bill Scanlon after an ankle injury. Bosch recalls that they carried him off the court on a stretcher and, a few days later, he had surgery on the ankle ligaments. „At first he did not even want to take painkillers, he was that stubborn. He kept his leg raised and I massaged it, ” remembers Bosch. But Becker wanted to come back so quickly that he resumed his daily training even though he had his foot in a cast. „We were playing on hardcourt, and he wore a metallic heel to be able to play. He played an hour, an hour and a half. Other players would not have done this. We played basketball with him, doing everything to keep him in shape. ”

Bosch also took him to a few tournaments in Austria, Germany and Switzerland to keep in touch with the competition, and all the efforts were worth it: Boris came back at the US Open junior tournament and looked good for the next season.

But on his favorite surface, at Wimbledon, exactly one year after his first injury, Becker stumbles again. Now it is in the fourth round against Tim Mayotte, after he managed to squeeze by in the previous match, 9-7 in the decider against the 7th seed, the Swede Joakim Nyström. Mayotte is up two sets to one, and at the end of the fourth set Boris trips as he had the year before. He gets scared, gestures that he can not go on. There is a video of it on Youtube. You can see Becker telling Bosch and Tiriac, who were seated behind the umpire’s chair, that he cannot go on. Tim Mayotte was still far back on the court, leaning against the tarp and Bosch had time to yell at Boris to ask for the physiotherapist. „He looked to me in amazement, as if I was crazy, but he changed his mind and sat down.”

Because he was playing on court 14, the doctor could not reach Becker during that break. Bosch told him to keep on playing and go for broke on every shot. “And Becker, being the beast he was, a guy with high tolerance for pain – he steps on his foot twice, sees it does not hurt too much, gets on the court and turns the match around! He then goes on to win Wimbledon. Everybody in Germany wondered: if he had withdrawn from this match, would he have had the career he had?” Bosch cannot answer this question. He says nobody can. „Anyway,” he muses, „many said he was too young to win at the age of 17. But I am telling you, tennis cannot be planned. Results cannot be planned. ”

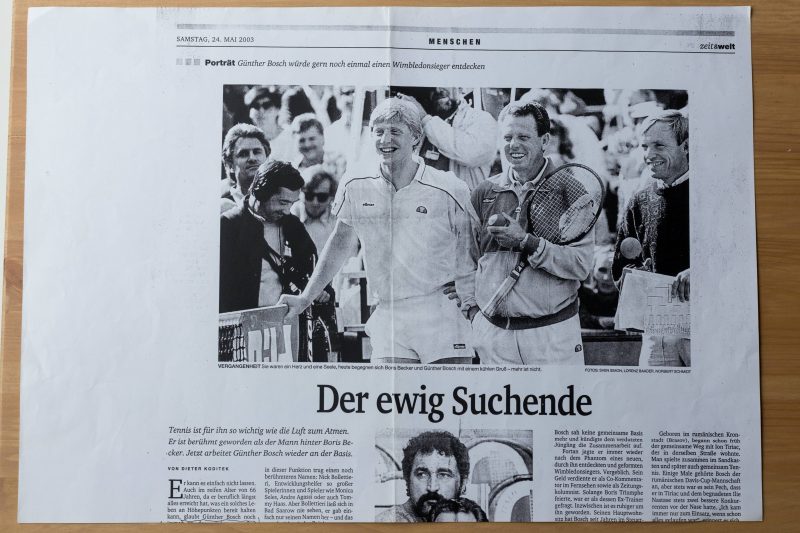

Becker played the final against the American Kevin Curren, the 8th seed who had brushed aside McEnroe and Connors, the main favorites. Becker won in four sets, becoming the youngest Wimbledon champion – 17 years and seven months. He was the new sensation of the tour, and the Bosch-Tiriac duo, who had helped him get there in record time, won over the Germans’ respect.

*

Bosch thinks that first Wimbledon title was very lucky and, career-wise, Becker’s second Wimbledon title, won in 1986, was even more important. „To maintain success is much harder than to get it. In order to repeat the success of ’85, I did everything in my power and I can say I played a crucial role in that. ”

In Becker’s life there was now a girl: Benedicte Courtin, from Monte Carlo, where Becker had moved his residence. Bosch, who had already begun to realize that he could no longer expect Becker to carry on with the same strict life regimen as before, says he helped Boris with this friendship. „In 1985, I spent only five days at home with my wife and my daughter. The rest, on the road with Becker. So I realized it was natural for him to have a romantic relationship and I explained to him how I see this. Together with my wife, we told him what love means … ” But the love of a 17-year-old star is not simple, and Bosch learned this pretty quickly when Boris met a tennis player in America and started a close relationship with her, too. „Basically, Boris had two girlfriends (smiles). My wife had to buy gifts for both of them. ”

And it was not the only complication: after Boris’s first Wimbledon, Tiriac wanted to get involved in his coaching. “Tiriac was really helpful. I cannot say a bad word about his behavior until Boris’s first Wimbledon title. But after that he changed a lot, „adds Bosch, then hesitates briefly. He takes off his watch and shows us the engraving: Günther Bosch, Wimbledon 1985, BB & IT. „I got a watch for each title, but my house got broken into and very few remained.” Then he returns to Tiriac, who, in the spring of 1986, tried to convince Becker that his style of play will never work on clay. „He said he needed to hit with more topspin, wait for the short ball and then, boom!” Bosch’s theory was different – no matter the surface, Boris had to play the same game.

Becker was stuck in the middle and did not know what to do. He lost in the quarterfinals at Roland Garros against an average player, the Swede Mikael Pernfors, who won the last two sets, two and zero. „It was a disaster, because we were there to win the tournament. Boris did not know how to play anymore and he blamed Tiriac for his confusion.” Bosch, who left with Becker for London to prepare the grass season, says Tiriac was not allowed to approach them anymore, not even at breakfast. But the damage was done. Becker lost to Tim Mayotte in Queens and, because his mind was no longer focused on tennis, he asked Bosch for permission to go to Monte Carlo, to meet Benedicte. „There was just one week until Wimbledon, so I told him we have to get ready, we cannot go home now. He tells me that if I let him go – it was Friday – he will take the first plane back on Monday and will do everything I tell him in practice. I said, ‘well, Boris, I’m okay with this, but you realize if Tiriac finds out what’s going on…”

Bosch recalls Tiriac’s reaction vividly. They were in the elevator when he told him and thought Tiriac would destroy it with his fists. „He is cursing and he tells me that if Boris loses here early, I’ll be a laughing stock as a coach, that I’ll never work again. Well, Boris played and won his second Wimbledon in a dominant fashion! ” In the final he beat Lendl, who had skipped all the clay tournaments to prepare for Wimbledon. „After winning, I stood up and applauded him, and Tiriac, who was behind me, slapped my back so hard I nearly fell over the people in front of me. ‘You were right! What you did, letting him go to Benedicte and all that, you were right. ”

Boris had won again, this time as a confirmation, and all that was written after the first Wimbledon was now blown up tenfold. The press used expressions as „this golden trio” to describe the relationship between Tiriac, Bosch and Boris, but Bosch says their relationship has not been the same since then. Tiriac was unable to reconcile with Becker, who did not want to see him at all, and Bosch was caught in the middle, trying to explain to Boris that he could not do that. „And the truth is, I started having problems with Becker,” says Bosch, who remembers the Dallas tournament, where Boris played semifinals against Stefan Edberg. „I told him that the only way you can pass this guy when he comes to the net is by hitting topspin lobs. Boris played them, but too short. And Edberg was smashing all the balls. The match was broadcast in Germany, and suddenly Becker walks towards the video camera and shouts Scheiß Trainer! And I tell Tiriac: „If he calls me that one more time, I am packing my bags and go home. I will not put up with this.” But he gets to the tiebreak, plays three topspin lobs, wins the points and the match, goes to the camera and says Mr. Beste Trainer der welt!, for everyone to hear. This was Becker! How long could one put up with that?”

Their break-up happened in 1987, immediately after Boris’s loss in the fourth round at the Australian Open, which was widely publicized. Suddenly, the fantastic team that had Becker in the center, coached by Bosch and managed by Tiriac, was no more. Only a few months had passed since the second Wimbledon title won by the blond wonder kid, so the press searched for reasons. Becker introduced them only later in his autobiography: he was tired of the parental image of his coach. When asked about the pain of separation, Bosch says „there was no suffering nor joy, it was just necessary.”

Most of Bosch’s story after the breakup with Becker revolved around the search for a second Boris. „In Germany everyone was waiting for a second Becker. And there has always been a buzz around my players – who is going to make it?” Bosch had enough candidates, many of them of Romanian origin. Christian Saceanu was born in Cluj-Napoca and emigrated to Germany at the age of 14. He was one of the youngest prospects in the new four-player group after Becker. In 1986, at the age of 18, he won the national junior championships and became world leader in his age category. He turned pro the same year, and the world had every reason to talk about the next star of German tennis. But Bosch knew that Saceanu was made of a different cloth from Becker. „Saceanu was able to practice for eight hours and ask me if it was enough. But he could not play under pressure. He asked me to practice on court 20, to get away from the people filling the stands. It was true, the stands were full because the world was waiting for the second Boris. But that Boris had been interested only in the ball coming his way. ”

Another player in Bosch’s group was Andrew Ilie, born in Bucharest, but representing Australia. He beat some top ten players, won two ATP titles and cracked the top 30. Bosch says he did not have many players with a better forehand than his. „And I have coached a few people in my day!” He thinks that the best of all was Markus Gabriel, an Argentinian of German origin who got to 36 in the world rankings in 1992. Bosch thinks Markus would have gone up even if he was not an … „a**.” He says it in jest, full of regret for his former student. „But it is true. Markus Gabriel played terrific tennis – I think he won against three or four top 10 players – but he did not have that desire to win, to go all the way.”

Bosch thinks the will to win is the most important thing on the tennis court, but it is a rare thing. „Dinu Pescariu was also in my team – it was called Panasonic at that time, it was sponsored by them. We had gone from four players of similar level to two seniors and two juniors.” They all practiced together, and that helped the juniors to develop. But Pescariu – with whom he started working after he made the semifinals in the Roland Garros junior tournament – did not have that desire that distinguishes the good players from the excellent ones. Bosch, who smiles as he remembers Pescariu, says he could write a book about all the pranks pulled by young Dinu. He realized then that the times were changing and that it would be more and more difficult to develop the kind of relationship he had with Becker at the beginning of 1985. „I have lived with this pressure from all Germany: the second Becker, the second Becker, the second Becker. And I thought I could have a second Becker, but I realized, little by little, that I cannot. 50 years from now, he will probably still be the only German player who won Wimbledon three times … twice with me. ”

*

Günther Bosch moved to Berlin in 2011 after 25 years of living in Monte Carlo, along with Rodica and Christina, his wife and daughter. „Christina studied Art History here. We had to take care of our health anyway, and here in Germany it is best.” Sitting on the terrace of the club where he coached in the last years of his career – last year, health problems stopped him – Bosch has a special aura, a contagious smile and loves to tell stories. He jumps from one topic to another, goes on tangents, lets slip a “scheiße” here and there when his memory does not serve him well, asks if you know such and such players and laughs when you tell him you’re too young to remember Nyström, Mayotte, Curren and the others. At Rot-Weiß, a elite tennis club, Bosch worked with his children groups at the highest level, because „I was so famous, not just because Becker, but because I have the ability to coach young people to become, to the best of their abilities, professional players. ”

But this reputation has not reached Romania, because Bosch has not returned here too often after the fall of communism in 1989. Lately, however, he has often thought about his hometown and the country he left. He is available for interviews, but the requests from the Romanian press do not come. „I’m not a star, I do not need to be one. But has everyone forgotten me? I expected some curiosity at least. Yes, I was coaching with the stick in my hand; I was asking you to climb the Tâmpa hill ten times. My methods are outdated, I know. But maybe tomorrow I won’t be anymore. Is there nothing worth keeping? ”

Bosch’s intention was that after everything he had done for his players, not just Becker, he would do something for Romanian tennis. He worked for seven years with Adrian Marcu at a tennis academy he founded along with other coaches at Bernau Wandlitz, near Berlin. Daniel Dobre was there, too, one of the coaches who recently worked with Simona Halep. „I thought they were my disciples, that I will leave the academy in their hands.”

It did not happen that way, and Bosch got out of that business in circumstances he wants to forget. Marcu and Dobre returned to Romania, where they both made a name for themselves coaching the female players who have turned Romania into a tennis superpower in the last five years. „I am happy for them and always wished them well. I do not miss a match, ” he says, before pulling out some of the main draws of the tournaments in progress covered with scores, notes and underlined ideas. „I know all the girls, Begu, Niculescu and the others, and I follow their results. I’m no longer on the court , but I don’t miss a thing.”

IBAN RO51RNCB0079145659320001

Asociația Lideri în Mișcare,

Banca Comercială Română